Almost everyone has heard of the famous Hundred Years’ War, which was fought in France in the 14th and 15th centuries. This long (as long as 116 years) and bloody series of armed conflicts between England and France began with English claims to the French throne. One of the first major clashes of armed battles of the period was the Battle of Crécy. In that battle, one smaller but disciplined army of English King Edward III defeated a French army – twice its size, but ineptly commanded, inflicting it.

Source: Julian Story [Domena Publiczna], via Wikimedia Commons

Before the battle

On August 26, 1346, an English army led by Edward III clashed with Philip VI’s French near Crécy, in northern France. Earlier, Edward’s forces had retreated north, pursued by Philip who wanted to catch up with them and engage in a battle on the Somme, which would have given France an advantage. However, the English managed to escape this trap and, overcoming the weak crossing defenses, made their way to the other side of the river at the last minute. Thus, it was Edward who secured the choice of the site of the future battle, on which he based his victorious strategy.

Before the battle, Edward and his army took up a position on a hilltop, which gave them a strategic advantage over the French. The English spent a full day building defensive lines complete with spur, palisade and wolf pits. They then deployed in three lines, each about 2 km long. In front of the first line, many deadly traps were placed, such as camouflaged pits, sharpened piles and metal stars that cripple horses’ hooves. The English knights unhesitatingly obeyed Edward’s order to stand up to fight alongside the regular infantry. One of the wings was commanded by the king’s son, the then 16-year-old Edward IV later known as the “Black Prince.”

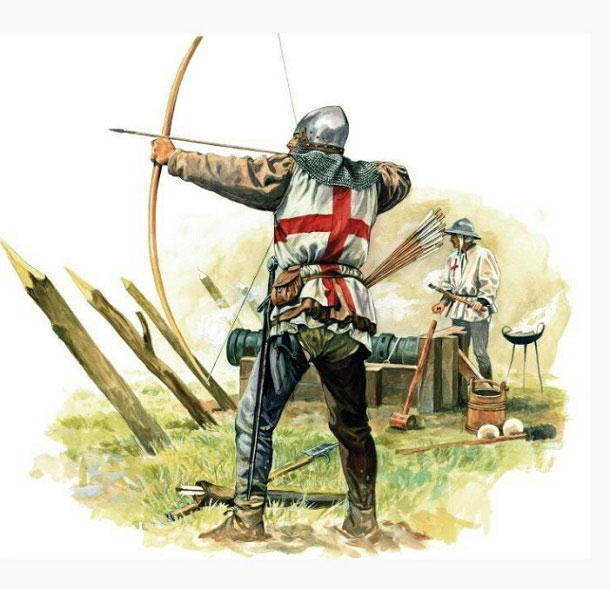

Source http://ringingforengland.co.uk/st-george/

Force comparison

The English forces numbered between 8,000 and 14,000 men, including 2 – 3,000 heavy-armed knights, 5 – 10,000 elite archers and about a thousand pikemen. They were also supplied with 3 cannons (and this is the first confirmed use of artillery on the battlefield in history), but their combat value was very low at the time – they worked quite well as psychological weapons instead.

English archers were one of the deadliest formations on the medieval battlefield. They were equipped with long bows made of yew wood, which could carry up to 300 meters and penetrated the knight’s armor at short range. However, the most important thing was their rapidity – a trained English archer was able to release 5-6 arrows per minute, while a crossbowman could shoot a maximum of two. These archers were true serial killers, and used correctly in battle (which happened very often) they were very difficult to stop.

The English were prepared and ready to accept the battle, a French army arrived on the fields of Crécy. Philip managed to gather 20 – 40,000 men, including, among others, 12,000 heavy knights and 6,000 famous mercenary crossbowmen from Genoa.

Source: http://ru.warriors.wikia.com/

Deadly charge and a hail of bullets

The battle began with a duel between crossbowmen and English archers. The mercenary Italian crossbowmen were known at the time for their excellent training and discipline. However, that day the Genoese squad hired by the French was exhausted after a long march, and to top it off, the strings of their crossbows got wet in the rain (the English had managed to hide their strings under their helmets). As if that wasn’t enough, the Genoese had left their pavises in camp – so they had no protection from enemy fire.

Despite all these adversities, mercenary crossbowmen were sent to attack the English lines and bravely launched an assault. However, they had to climb up the slope in low visibility, as the sun shone directly on them. By some miracle, the Italians managed to fire the first salvo, but this one did not reach the English lines. At the same time they were already under fire from Edward’s archers, whose arrows quickly began to take a bloody toll among them.

The Genoese commander, seeing the deaths of dozens of his men, ordered a quick retreat. However, when King Philip of France saw his mercenaries fleeing the battlefield, he ordered his knights to quickly strike at the first lines of the English. However, the knights did not wait for the return of the crossbowmen, whom the French charge literally massacred.

The French attack, uncoordinated and unorganized after killing many allied mercenaries, was unable to break through English lines and entanglements. The knights charged 16 times, dying under a hail of English arrows, drowning in the swamp and dying in wolf pits. Only a few groups of Frenchmen managed to reach the enemy, but these were quickly annihilated by Welsh and Irish pikemen.

Source: http://www.nationalturk.com/

After the battle

Many high-born Frenchmen and their allies died that day, and one of them was the Bohemian King John of Luxembourg. This 50-year-old blind warrior who, on the fields of Crécy, ordered squires to tie themselves to two knights and died during the assault, choosing death over dishonor.

The Battle of Crécy is a rare example of a victory by a smaller army over a much larger one. Its outcome was determined by excellent training and discipline in the army, as well as Edward III’s use of terrain and anticipation of the enemy’s movements. French losses were enormous – more than 1,500 knights and several thousand infantry remained forever in the fields near Crécy. The English lost only 100-300 soldiers and … a lot of arrows. Some historians consider this battle the beginning of the end of the cavalry era in Europe.

After winning at Crécy, Edward III besieged and captured Calais. However, no one expected that the Hundred Years’ War was just beginning….

Finally, a fun fact

A fact reminded to me by a colleague – everyone knows what the gesture of showing an extended middle finger, the so-called “f*ck”, looks like. This gesture dates precisely from the Hundred Years’ War, and it was originated by English archers displaying their hands with one finger towards the enemy before a fight. It originated from the fact that when the French succeeded in capturing such an archer, they immediately cut off his fingers with which to draw the bowstring. The gesture of the straightened finger (which one still possessed) was an attempt to provoke and anger the opponent.