Destination – Egypt!

The year 1797 was extremely successful for France. Its Army of Italy, commanded by the young general Napoleon Bonaparte, contributed to the conquest of northern Italy and the lands on the western bank of the Rhine. The same Bonaparte also negotiated a very favorable peace treaty with Austria for the French.

Napoleon’s achievements were so impressive that the members of the French Directory (the executive power in revolutionary France) began to fear the general, worried about their own positions. They immediately decided to assign him an impossible task in order to undermine his standing among the public. There could be only one objective, and that was, of course, the invasion of England—France’s greatest rival.

As soon as Napoleon inspected his army stationed in northern France, he quickly realized that an attack on the British Isles was practically impossible. He knew that naval superiority was essential, but the unrivaled English sailors dominated the seas and would never allow Bonaparte’s ships to approach their homeland. Therefore, he devised two alternative invasion targets: the occupation of Hanover or the conquest of Egypt. The latter option seemed to offer nothing but advantages.

First, controlling the Suez Canal would severely disrupt British trade with India, dealing a significant blow to their economy. Second, establishing a colony in Egypt was meant to compensate the French for their previously lost colonies. Third, beyond military and economic objectives, the expedition also had a scientific purpose, bringing along a group of scholars—including mathematicians, engineers, astronomers, naturalists, geographers, chemists, architects, and many other educated Frenchmen.

Wikimedia Commons

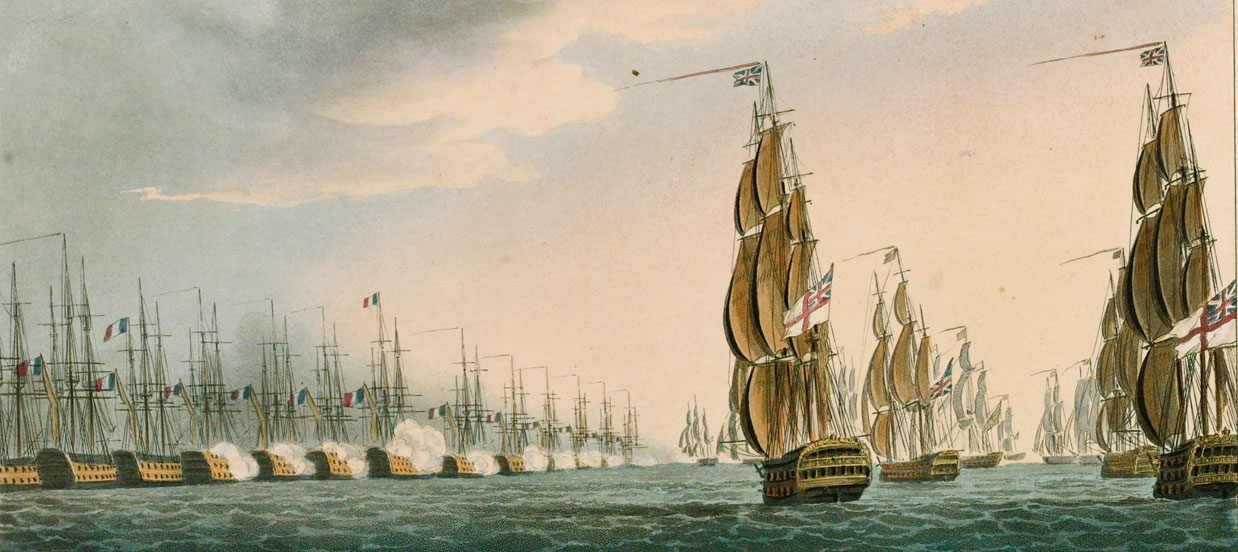

Napoleon’s proposal was accepted and preparations for the invasion quickly began. 54,000 men were taken on the expedition, including 13,000 sailors of the navy and 3,000 of the merchant fleet. The rest were mainly more than 34,000 soldiers, concentrated in half-brigades of infantry, cavalry, artillery and others. As for the fleet, 72 warships sailed to Egypt. The core consisted of ships of the line, such as the flagship L’Orient, Guillaume Tell, Franklin, Tonnant, Spartiate, Genereux and others. In addition, the invasion fleet included excellent frigates, corvettes, as well as smaller vessels. All these ships were divided into three squadrons and an escort convoy. Admiral Francois-Paul de Brueys became the fleet’s commander, and at the same time took charge of the “red” squadron on L’Orient. The “blue” squadron was commanded by Rear Admiral Blanquet du Chayla on Franklin. The last squadron had under orders, known to us from under Trafalgar, Rear Admiral Pierre Charles Villenueve on Guillaume Tell.

The fleet set sail on May 19, 1798, heading toward Malta, whose central location allowed for control over all Mediterranean shipping. Along the way, the island—then under the possession of the Order of St. John—was seized by Napoleon’s soldiers, who carried out necessary ship repairs and replenished supplies.

Next, the French fleet set course for Crete, where bad weather forced a 24-hour stopover. As it later turned out, this delay saved Bonaparte’s ships, as it caused them to narrowly miss a confrontation with British Admiral Nelson.

The French fleet reached the Egyptian coast on June 29. The landing was to be carried out near the port of Alexandria, but the plan was hampered by very bad weather and high tide. French officers advised Bonaparte to wait out the poor weather conditions, but he firmly refused.

“We don’t have a moment to lose, fate has given us only three days. If I don’t use them properly – we are doomed!”

He was referring here to Nelson’s fleet, which could arrive at any moment. Despite these adversities, the French infantry launched an assault on Alexandria and quickly captured it, but then a serious problem arose, as it turned out that ships of the line and frigates could not enter the Alexandrian port, which proved to be too shallow for them. It was quickly decided to move the army to Aboukir Bay, more than 20 kilometers from Alexandria, and the French began to camp there as early as July 7.

Bonaparte and the other French commanders did not know that Aboukir would soon be the place where their proud fleet would perish.

Royal Navy in pursuit of the French

Lemuel Francis Abbott via Wikimedia Commons

Against Napoleon’s fleet, Britain sent a squadron commanded by none other than the famous Sir Horatio Nelson – one of the most distinguished naval commanders in history, a brilliant strategist, adored by his own soldiers and feared by his opponents. First Lord of the Admiralty Lord Spencer wrote to Count St. Vincent (commander of the English fleet in the Mediterranean) about sending Nelson in pursuit of the French this way: “I rejoice to send Sir Horatio to you, not only because I am convinced that I could not have found a better, more capable, and more devoted officer, but also because I know how much you wished to have him under your orders.” Such a recommendation said a lot about the skills of the later conqueror of the French fleet.

Nelson and his squadron had known from the start that the French had set sail. The English were determined to find Bonaparte’s ships and engage them in battle, but they were unaware of the expedition’s destination. As a result, they roamed the Mediterranean, first missing the French landing near Alexandria and then failing to spot their fleet entering Aboukir Bay. When the delayed Nelson finally saw the French ships off the coast of Egypt, he was devastated. He decided to engage the core of Napoleon’s fleet, which was stationed at Aboukir.

“Before this time tomorrow, I shall have gained a peerage, or Westminster Abbey.“

Preparations for the coming clash have begun on English ships.

Comparison of the strength of the two fleets

No one doubts that at that time the British Navy was the strongest navy in the world. It consisted of nearly 500 warships of various types, of which as many as 146 were ships of the line, that is, vessels performing a similar role to battleships in the early 20th century. British commanders were experienced and reliable, and the ships’ crews were well-trained – for example, under Aboukir, gunners serving on Royal Navy ships fired with three times the frequency of French ones. For good reason, English sailors had an unshakable sense of their superiority over the French.

The French fleet, although it also had a long and at times glorious history, was far from its peak during the Napoleonic era. The recent French Revolution had led to the death or exile of many skilled officers, while the warships were rotting in ports. The process of rebuilding had begun, but despite this, at the mouth of the Nile, the crews of the French giants were incomplete and less trained than the British.

In Aboukir Bay, Nelson had 13 ships of the line (each had 74 guns) and two smaller vessels, probably a frigate and a brig. The French had a similar force – 13 ships of the line and four frigates went into battle.

Thomas Sutherland via Wikimedia Commons

“Leave me here, in the middle of the battlefield. This is the best place for a sailor’s death!”

Both fleets clashed on August 1, just before sunset. The French commander-in-chief, François Paul de Brueys d’Aigalliers, had great respect for Nelson and carefully studied his past tactics before the battle. Not wanting to give the English a chance to encircle his forces, d’Aigalliers anchored his ships in a battle line, aiming to create a stationary wall of fire and prevent Nelson’s forces from engaging in close combat. The French were protected by a sandbank on one side, while on the other—where they expected the attack—lay the open sea.

The French commanders were convinced that the battle would not begin before sunset and would only start in the morning, so their preparations were slow and chaotic. Disorder reigned on the decks, and as it later turned out, the French ships were overloaded with supplies on the port side (left), which meant that during the battle, they could fire at the English almost exclusively from their starboard sides!

Initially, the French gunners opened fire first, while the English ships passed them, waiting for the opportunity to engage at closer range. The first ship in the English line, Goliath, anchored behind the second French ship-of-the-line, Conquérant, but during the maneuvering, she was attacked by the frigate Le Sérieuse. The devastating salvos from the 74-gun giant quickly wreaked havoc on the frigate, though it was ultimately the fire from the third ship in the line, Orion, that nearly destroyed Le Sérieuse and forced her to run aground. The following day, her crew surrendered the ship.

The first ship in the French line, Le Guerrier, defended herself against two English ships: Zealous and Theseus. In the first ten minutes of the fight, Le Guerrier lost all her masts, even though she was only being fired upon by Zealous and managed to reply with only a single broadside from her port side. Once Theseus began firing as well, the French ship quickly became a floating wreck and surrendered later in the evening, having lost more than half of her crew.

The already mentioned Goliath launched an intense bombardment on Conquérant, which had her gun ports blocked and was unable to fire for several minutes. To make matters worse, every passing English ship fired a broadside at the French vessel. Conquérant surrendered at 9:00 PM, having lost all her masts and most of her crew.

The crew of the ship-of-the-line Peuple Souverain earned a place of honor in the history of the French navy. Attacked by three English ships—Orion, Defence, and Goliath— she fiercely defended herself until 11:00 PM and surrendered only at 3:00 AM

Nelson’s flagship, Vanguard, engaged Spartiate, the third ship in the French line. Unfortunately for Vanguard, she approached from Spartiate’s starboard side—the very side where most of the French ship’s cannons and crew were concentrated. To the great surprise of the English, the French vessel inflicted heavy losses right at the start of the battle. The first broadside alone killed 35 men on the flagship, and subsequent volleys increased the casualties to 70.

Image: Nicholas Pocock, Wikimedia Commons

Nelson himself did not escape injury—he was struck by a splinter in the forehead, causing his face to be quickly covered in blood, and had to be carried below deck for treatment. Interestingly, this famous naval commander refused to announce himself at the wound treatment station and patiently waited for his turn. Vanguard fought a brutal duel with Spartiate until 11:00 PM, and it likely would have lasted even longer had the French ship’s captain not been wounded and unable to continue commanding. Despite the victory, the English flagship was so badly damaged that it had to sail to Naples for repairs immediately after the battle.

British ship of the line Minotaur, after firing broadsides at Spartiate, engaged in a duel with L’Aquilon, the fourth ship in the French line. The battle, initially evenly matched, was interrupted when the French commander, Captain Thevenard, was killed. At 8:30 PM, L’Aquilon struck her colors and surrendered.

The most frequently mentioned duel at Aboukir was the brutal battle between Bellerophon, ninth in the line, and the French flagship, the massive L’Orient. Despite the French ship’s overwhelming superiority, the English captain, Commander Henry Darby, considered it an honor to face such a giant. Within the first hour of this ferocious fight, Bellerophon suffered 43 killed, 150 wounded (including its commander), and lost two masts. The English ship was slowly turning into a wreck, and to avoid sinking, the crew cut the anchor cables, allowing the vessel to drift out of enemy gun range.

During the exchange of fire, Vice Admiral de Brueys was also wounded, suffering severe injuries to his head, arm, and hip. By the end, a cannonball tore off his leg. When he was offered the chance to leave the deck, the brave Frenchman refused. Shortly afterward, he was killed by a cannonball fired from Alexander or Swiftsure, which had approached the French flagship and set it ablaze.

At 9:00 PM, L’Orient caught fire, and an hour later, despite the crew’s desperate firefighting efforts, she exploded. In an instant, the largest ship of the French fleet ceased to exist. The blast was so powerful that burning debris rained down on nearby ships. Out of a crew of 1,010, only 60 survived. Among the dead was the ship’s commander, Commodore Casabianca, who refused to abandon the vessel, believing that his 10-year-old son, Jacques, was still below deck. As it later turned out, the boy had already escaped the ship before the explosion, but he did not survive the night.

French ship of the line Tonnant, anchored behind L’Orient, managed to escape from the attacking Majestic, but it ran aground and struck her colors on August 2. Under fire from three English ships, a total of 178 guns, the French ship of the line Franklin surrendered at 11:30 PM.

Thomas Luny via Wikimedia Commons

When the battle was already lost, Rear Admiral Villeneuve signaled the surviving ships to escape. In the end, only his flagship, Guillaume Tell, along with Généreux and two frigates, managed to flee from Aboukir. The remaining French ships were not so fortunate: Timoléon was so badly damaged that her own crew set it on fire, while Heureux and Mercure ran aground and surrendered to the English.

The battle was over. The victory of Nelson’s ships was total – with the loss of only 218 men and 677 wounded, the English captured 9 and sank 2 French ships. 1,700 Frenchmen were killed, 600 were wounded and 3,000 were taken prisoner. The few who escaped from the carnage supplied Napoleon’s army in Egypt.

After the battle

How did it happen that the French fleet was so devastatingly defeated, with practically no chance for anything beyond desperate defense?

First, this was due to the poor strategy of Admiral de Brueys, who positioned his ships too far from the shore, creating a gap that the English ships exploited. Their formation also worked against them—five French ships were unable to join the battle.

Second, the battle was fought on Nelson’s terms, as his exceptional tactical instincts allowed him to identify and exploit the enemy’s weaknesses. His plan was both bold and simple. Its successful execution was also a result of the excellent training and high morale of the English sailors.

For his victory, Nelson was awarded the title of Baron, a pension of 2,000 pounds sterling to be paid for three generations, and a coffin made from the salvaged mast of the French flagship L’Orient. The supremacy of the Empire at sea was preserved. Seven years later, at Trafalgar, the heroic admiral—one of the greatest naval commanders of all time—gave his life once again shattering the power of the French fleet.